Leader Character Shows Up in Hard Numbers—of Success or Failure

The world has been rife with highly visible leadership fiascos stemming from leaders with character deficiencies that induce, influence, or propel poor judgment: fraudulent Volkswagen emissions standards; risk management processes that facilitated the Boeing 737 MAX problems; and governance practices at Wells Fargo that allowed sales-tactics violations, to name only a few. The cost – both human and financial – of character-related transgressions for these organizations and their related stakeholders has been substantial.

For over 15 years, starting with the financial crisis in 2008, a central question guiding our research is: why we don’t take character more seriously when it comes to leadership and leadership development? Why is the focus on leader character often minimized, or is it relegated to the category of “soft skills” or a nice-to-have rather than a must-have? When will we collectively recognize the consequential impact of a leader’s character on individual and organizational well-being and start to elevate character alongside competencies and commitment in leadership practice? The evidence is clear: these “soft skills” equate to hard numbers—of success or failure.

Measuring Leader Character

Academic studies have shown that character is related to performance measures including, but not limited to, executive performance, innovation, subjective well-being, stress-coping responses, customer retention, and ethical decision-making. While many CEOs and board members believe character is essential in individual, team, and organizational excellence, they like to see actual data showing to what extent character contributes financially to organizational performance.

Fred Kiel found that CEOs with strong character brought in a nearly five times greater return on assets than CEOs with weak character. In addition, the former enjoyed a 26 per cent higher level of workforce engagement and their corporate risk profile was much lower. In a study of a Fortune 500 manufacturing organization, Gerard Seijts showed that there is a sizeable return on investment associated with the use of character assessments in employee placements: $21,422 CAD per year over a 15-year tenure for low complexity jobs and $37,609 CAD for high complexity jobs. Adam Grant reported that growth and success in life is not about the cognitive skills that individuals possess – it is about the character skills that they develop starting in kindergarten. Character skills are about 2.5 times more important than cognitive skills in determining how much money individuals earn in their 20s. This pattern of results was replicated with African entrepreneurs: individuals who were taught character skills ended up growing their businesses more successfully than those who were taught cognitive skills. These are important numbers that cannot be overlooked.

Our work on character is based on good scholarship. Academics have many roles and responsibilities and one of them is to help in the improvement of society through science: the creation and dissemination of new knowledge and new understanding. As astrophysicist and science communicator Carl Sagan shared, "Science invites us to let the facts in, even when they don't conform to our preconceptions. It counsels us to carry alternative hypotheses in our heads and see which best fit the facts. It urges on us a delicate balance between no-holds-barred openness to new ideas, however heretical, and the most rigorous skeptical scrutiny of everything — new ideas and established wisdom. This kind of thinking is also an essential tool for a democracy in an age of change."

Therefore, being engaged in public discourse is part of our obligation to society and to help inform public debate in myriad areas: social, political, technological, medical, and so forth. This is an opportunity we relish. We have seen the difference character makes – in individual lives as well as the fate of groups, organizations, communities, and societies.

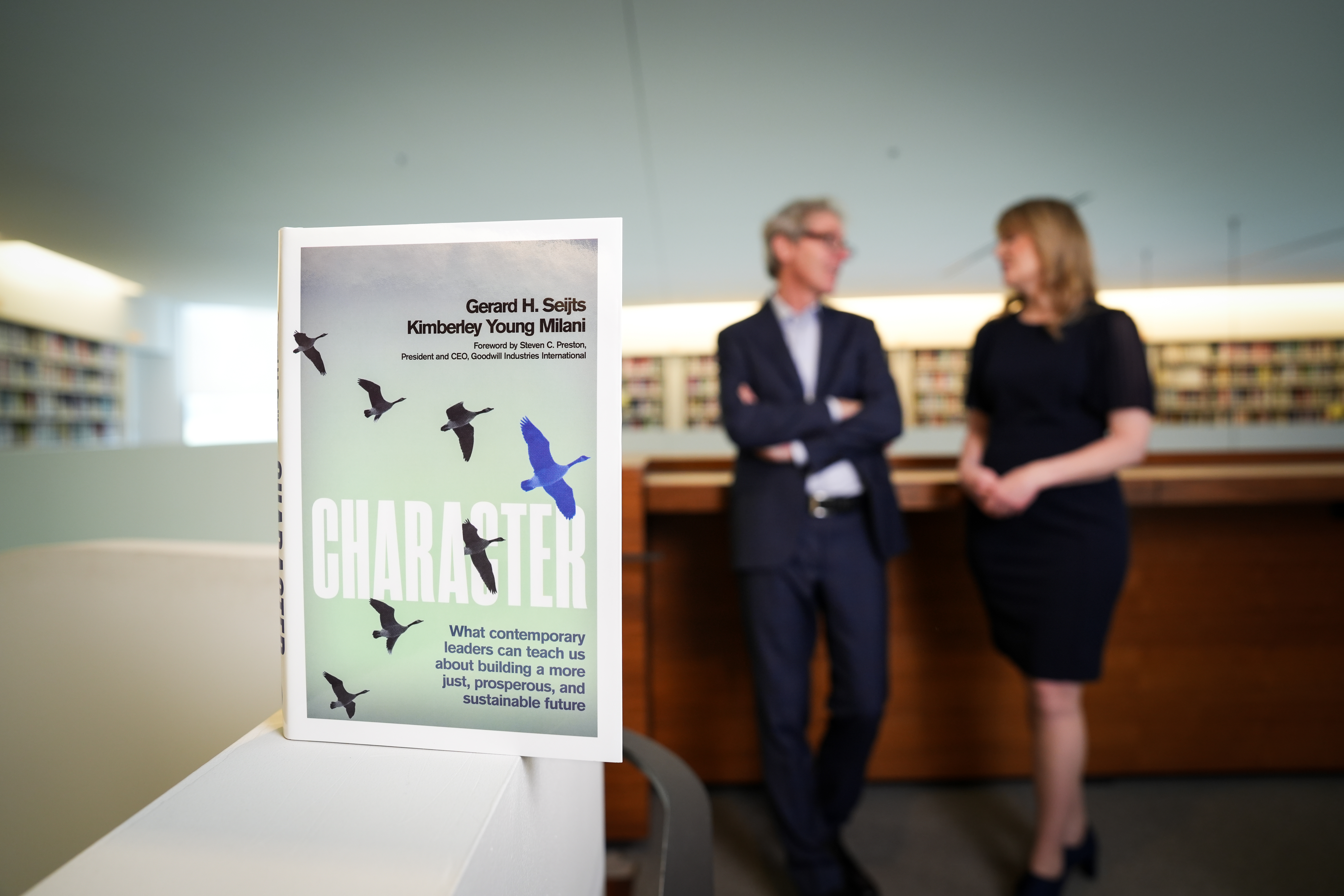

Yet, for decades, the issue of character—once a central tenet of education—has been largely absent from the curriculum and the discourse on leadership. We can do better. We must do better. This is why, in our most recent book, Character: What Contemporary Leaders Can Teach Us About Building a More Just, Prosperous, and Sustainable Future, we make the case for character.

Character Leadership in Practice

Defining Leader Character

First, we outline the meaning of character as there is often ambiguity surrounding what the word means and how it functions. Character reflects who people are, rather than their skills or talent. It deeply influences one’s judgment and the choices people make in any given situation.

Our research has shown that individuals must be able to exercise the following dimensions of character in levels that are contextually appropriate to arrive at sound judgment: accountability, collaboration, courage, drive, humanity, humility, integrity, justice, temperance, and transcendence. Character is the essence of our being that determines whether it is our best self (or not) who shows up each and everyday – as a leader, citizen, parent, community member, and so forth.

We argue that competencies and commitment – largely the key themes of most leadership titles and executive education – are underpinned by character. Character directly affects a leader’s decisions about whether they will acquire the requisite competencies for their role and if they will make the commitment to lead in a sustained and effective manner. As Adam Grant put it: “We all know people who have great cognitive skills and were not able to make good use of them because they lack character skills: they avoid discomfort, they can’t take feedback, and in many cases, they end up becoming so perfectionistic that they lose the forest in the trees.” Thus, no level of competence or commitment will work to potential without strong, well-developed character. Character, therefore, is the bedrock of leadership.

Developing Leader Character

Second, we highlight how individuals can and indeed are developing their character, for better or for worse, every day — how it is critical that we bring awareness and intentionality to the development of character to strengthen each dimension and maximize their individual and collective effectiveness. We show how character development does not happen in a vacuum and can be supported or influenced by families, sports, academic institutions, professional associations, religious or spiritual communities, the arts, volunteering, and other entities within one’s life. In organizations, character also drives culture and conduct and, therefore, should be brought into processes such as recruitment, selection, assessment, reflection, coaching, mentoring, succession management, and a host of other initiatives.

Using Character to Navigate Complex Challenges

Third, character must be present if individuals and the organizations they work for, or lead, are to be successful in the environments in which they operate. We are in an era of converging crises. The environments within which we are all operating are in a state of constant uncertainty, disruption, and flux. Strength of character generates the agility and the creativity to address the myriad challenges we face, the fortitude and resilience to bear hardships, and the ability to remain curious, wonderous, and even delighted by this extraordinary world we live in.

Character Drives Positive Outcomes at Multiple Levels

Finally, as revealed in both rigorous academic research and the interviews with distinguished leaders presented in the book, the outcomes that result from well-developed character yield vital benefits to individuals, teams, organizations, communities, and societies. There is nothing “soft” about character, rather it is robust, critical, and consequential aspect of leadership. It enriches how we experience our personal and professional lives – individually and collectively – thus justifying the attention the construct deserves in the leadership discourse, as well as the need to return to a conscious and concerted effort to develop character as a habitual practice – in education and in business leadership.

While the leaders featured within our book have an elevated profile compared to most of us, we hope that their stories can help you to connect to elements of leadership that are universal and in which you can see yourself, be inspired by their character so that you can weave their insights into your own leadership practice, stir your imagination about a world filled with possibility, understand the importance of engaging in simple acts — those small everyday deeds — that can help us to turn the tide, to undo past harms, or to create new ways of being that can lead us towards a future with greater human and planetary flourishing.

Gerard Seijts is Professor of Organizational Behavior at the Ivey Business School. Kimberley Young Milani is the Director of the Ian O. Ihnatowycz Institute for Leadership at the Ivey Business School. Their new book, Character: What Contemporary Leaders Can Teach Us About Building a More Just, Prosperous, and Sustainable Future, shares research insights on Leader Character and features interviews with individuals who have demonstrated incredible leader character. The book, released on April 30, 2024 is available for order now.

About the Book

The latest book from the Ian O. Ihnatowycz Institute for Leadership provides an exceptional opportunity to become a better leader by applying the extraordinary yet down-to-earth insights from the authors’, Gerard Seijts and Kimberly Young Milani, accessible scholarship and interviews with truly distinguished leaders whose lessons on building stronger societies through character-based leadership are moving, powerful, and evergreen.

Rated Amazon's #1 Best Seller in Business Ethics, you can order your copy of Character: What Contemporary Leaders Can Teach Us About Building a More Just, Prosperous, and Sustainable Future:

Give us a call 1.800.948.8548

Give us a call 1.800.948.8548